CIBSE Case Study: Bosco Verticale

This article originally appeared in the March 2015 edition of the CIBSE Journal written by Alex Smith.

Contents[hide] |

[edit] Introduction

The drama of Bosco Verticale's forested facade may be gaining international attention, but it is the innovative use of heat-pump technology that is helping to slash heating and cooling costs at these seminal Milanese apartment blocks.

The 19 and 27-storey towers of Milan’s Bosco Verticale apartment block came into full bloom for the first time last summer. Hundreds of varieties of trees and shrubs spilled over the balconies of the 111 apartments to ensure the scheme lived up to the promise in its name, Bosco Verticale, Italian for ‘vertical forest’. The external appearance of the towers follows the seasons, and when you approach in mid-winter, after the deciduous trees have shed their leaves, the verticale is not so verde. Indeed, it’s difficult to distinguish the outline of the branches against the building’s dark façade.

While the towers may lose their ‘herb appeal’ during the colder months, the choice of deciduous trees is an important part of the environmental strategy. In the winter, the bare branches allow the sun to warm apartment interiors through the large floor-to- ceiling windows, so reducing the heating requirements. In the summer, trees in full leaf provide shading, which minimises solar gain and reduces cooling needs.

It’s an elegant and simple concept, which cuts the buildings’ energy use, while providing Milanese with a green vertical oasis in the city’s built-up centre. However, the trees are only one part of the innovative environmental strategy for the project. Designed by architect Stefano Boeri, the project is one of a number of new schemes in the Porta Nuova district of Milan that take advantage of a large aquifer under the city for heating and cooling. These include the Unicredit skyscraper, the tallest building in Italy.

Using ground source heat pumps to access the aquifer, the building services engineer, Planning, known in the UK as Rethinking Energy, is balancing the cooling and heating demands to minimise energy use at Bosco Verticale. Hilson Moran, the original building services engineer on the project, specified two Climaveneta Integra units, which can each provide 556 kW of cooling and 589 kW of heating. They have the ability to simultaneously provide heat and cooling, so, for example, hot water for underfloor heating can be provided to heat north-facing rooms, at the same time as apartments in south-facing rooms are cooled via ducted fan coil units. The radiant floor is also cooled through a heat exchanger connected to the aquifer loop, which helps lower the overall cooling load. Air handling units are positioned at the top and bottom of the larger tower to balance air flows.

The heat pumps work most efficiently during the spring and autumn, when different rooms in the tower need to be cooled and heated simultaneously. When the unit provides cooling for overheating rooms, the heat rejected from the condenser can be used to bring room temperatures in other parts of the towers up to the desired setpoint. By recovering heat and cooling simultaneously, the units can balance the cooling and heating loads, and can improve the COP (coefficeint of performance) of the heat pump.

To measure the efficiency of the units, Climaveneta uses the total efficiency ratio (TER), which is the ratio of the sum of the heating and cooling power, and electrical output. The coefficient of performance is usually used to measure the efficiency of heat pumps, but this is a ratio for either heating or cooling, not for both. Two small gas boilers in a basement plant room, rather than the heat pumps, provide domestic hot water, because, when the building was designed, it was felt that maintaining the gas boilers’ ability to keep water temperatures above 60°C was the best way to prevent the growth of legionella bacteria.

Planning building services engineer Giuseppe Medeghini says he would consider using a heat pump to supply domestic hot water if the building was being designed today, even though they can only provide water up to 45°C. ‘There are now ways to prevent legionella using chemicals, and they are cheaper and more effective,’ he says. ‘Using a heat pump works particularly well during the summer months, where all the excess heat coming from the cooling process, can be captured and used to provide domestic hot water .’

Medeghini says he would also consider using a second heat pump to produce domestic hot water up to 65°C, thereby doing away with the need for a storage vessel. ‘We now have much more flexibility in choosing a system for domestic hot water,’ he says’. Heat pumps still have a part to play in providing domestic hot water at Bosco Verticale. They pre-heat water to 45°C , so the gas boiler doesn’t have to work so hard to boost the temperature to the required 65°C. Planning is currently finishing the commissioning phase of Bosco Verticale, and is hoping to secure an ongoing contract with the developer, Hines.

‘Continuous monitoring is very important, especially on complex systems,’ says Medeghini. ‘Modern HVAC systems can bring important reductions in energy use, but they must be monitored and tweaked to guarantee these savings.’ The energy company is currently keeping tabs on a Climaveneta air source heat pump system at Palazzo Aporti, a Hines office refurbishment in central Milan. Using the heat pump manufacturers’ Clima Pro online monitoring system, the facilities managers can constantly access the performance of the heat pumps and the temperatures in the tenanted spaces, which are all metered.

If Bosco Verticale has the same technology, Medeghini says that the HVAC system can be continuously optimised, reducing energy use and cutting tenants’ bills. These savings will at least help the residents pay for the pruning of the thousands of trees and plants that have helped create Milan’s showstopper. While the foliage is fabulous, the intelligent design of the HVAC cannot be overestimated when considering the impact on carbon reduction at Bosco Verticale. Medeghini estimates the system offers at least 35% savings over a traditional building.

[edit]

Bosco Verticale is part of Milan’s Porta Nuova regeneration zone, which comprises a mix of retail, commercial and housing units, including the Cesar Pelli-designed Unicredit Tower, which at 231m is the tallest building in Italy. All the buildings on the estate use the same geothermal system as Bosco Verticale. There are three geothermal water loops on Porta Nuova. On the ‘Garibaldi’ loop serving Bosco Verticale the water is extracted from 12 underground wells, and transported via a 350mm distribution ring. The apartment blocks use the same loop as the nearby offices occupied by Google .

On the other side of the railway, another geothermal loop caters for the Unicredit Tower, plus a mix of other offices, retail and residential units. Water is filtered, before passing through heat exchangers under Bosco Verticale and the office. Secondary circuits in the heat exchangers take the chilled and hot water from a basement plant room into the buildings.

The combined peak heating loads for Bosco Verticale and the Google office is expected to be 2,200kW, and the cooling load 1,400kW. Water from the Garibaldi loop is discharged into the Martesana canal, unless its levels are too high, in which case the water is deviated to six wells that lead back to the aquifer. Permission for using the aquifer is lodged with the Milan province. It can take a year to receive a final licence, so these are lodged early in the construction process. The applicants have to state the amount of water they want to use in a year, and ensure that the return temperature of the water is within acceptable parameters. At Bosco Verticale the upper temperature limit is 25°C.

[edit] Balancing act

Planning is working on another scheme in Milan that uses a 150m3 sprinkler tank to store and recover heat and cool it from water in the system before returning it to the aquifer. This reduces the amount of water that needs to be pumped from the aquifer. ‘If the pool is between 10°C and 20°C, we do not use the aquifer. If it’s above or below, then we use the aquifer to rebalance,’ says Planning building services engineer Giuseppe Medeghini. ‘In the early part of the day, when heat is required in the rooms, the system cools the sprinkler tank water from 15°C to perhaps 11°C. The heat pump then doesn’t have to work so hard when cool air is required later in the day, when outdoor temperatures rise.’

[edit] Branching out

The balconies of Bosco Verticale are planted with 800 trees, between three metres and nine metres tall, 5,000 shrubs and 11,000 perennials. The trees, chosen by landscape architect Laura Gatti, are mainly deciduous, which means the external appearance of the two towers alters as the leaves change colour over the seasons. The trees will grow to 9m in height and then stabilise.

The plants are watered automatically through a centralised system that reuses water extracted from the aquifer. The greenery is maintained from balconies and external platforms, which are used for pruning hard-to-reach branches. Plant maintenance costs are covered in the

For the full article on the --CIBSE website click here.

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

- British post-war mass housing.

- Compact sustainable city.

- Creating strong communities – measuring social sustainability in new housing development.

- Densification.

- Eco Town.

- Garden cities.

- Garden town.

- Green belt.

- Lyons Housing Review.

- Masterplanning.

- Smart cities.

- The compact sustainable city.

- Regenerative design.

- Vertical Forest.

Featured articles and news

BSRIA Statutory Compliance Inspection Checklist

BG80/2025 now significantly updated to include requirements related to important changes in legislation.

Shortlist for the 2025 Roofscape Design Awards

Talent and innovation showcase announcement from the trussed rafter industry.

OpenUSD possibilities: Look before you leap

Being ready for the OpenUSD solutions set to transform architecture and design.

Global Asbestos Awareness Week 2025

Highlighting the continuing threat to trades persons.

Retrofit of Buildings, a CIOB Technical Publication

Now available in Arabic and Chinese aswell as English.

The context, schemes, standards, roles and relevance of the Building Safety Act.

Retrofit 25 – What's Stopping Us?

Exhibition Opens at The Building Centre.

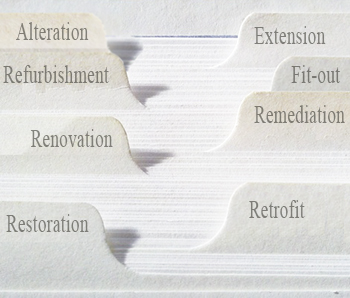

Types of work to existing buildings

A simple circular economy wiki breakdown with further links.

A threat to the creativity that makes London special.

How can digital twins boost profitability within construction?

The smart construction dashboard, as-built data and site changes forming an accurate digital twin.

Unlocking surplus public defence land and more to speed up the delivery of housing.

The Planning and Infrastructure Bill

An outline of the bill with a mix of reactions on potential impacts from IHBC, CIEEM, CIC, ACE and EIC.

Farnborough College Unveils its Half-house for Sustainable Construction Training.

Spring Statement 2025 with reactions from industry

Confirming previously announced funding, and welfare changes amid adjusted growth forecast.

Scottish Government responds to Grenfell report

As fund for unsafe cladding assessments is launched.

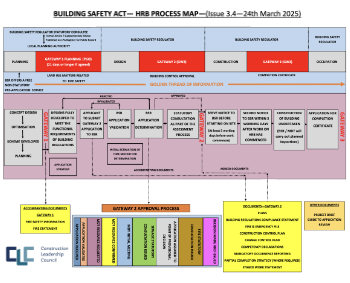

CLC and BSR process map for HRB approvals

One of the initial outputs of their weekly BSR meetings.

Building Safety Levy technical consultation response

Details of the planned levy now due in 2026.

Great British Energy install solar on school and NHS sites

200 schools and 200 NHS sites to get solar systems, as first project of the newly formed government initiative.

600 million for 60,000 more skilled construction workers

Announced by Treasury ahead of the Spring Statement.